Unit 5 - The History of Money (in the U.S.)

Learning Objective: Understand and be able to explain the transformation of commodity money to representative money to fiat currency as it occurred in the United States of America.

Unit Outline

5 The History of Money (in the U.S.)

5.1 Money in Colonial America

5.2 Continental Currency

5.3 The Coinage Act of 1792

5.4 The Coinage Act of 1834

5.5 The Coinage Act of 1849

5.6 The Coinage Act of 1857

5.7 Greenbacks and The Legal Tender Act of 1862

5.8 The Coinage Act of 1873

5.9 The Gold Standard Act of 1900

5.10 The Federal Reserve Act (1913)

5.11 The Emergency Banking Act (1933)

5.12 Executive Order 6102 (1933)

5.13 Gold Reserve Act (1934)

5.14 WWII and The Bretton Woods Agreement (1944)

5.15 Bread, Circus, and War (1960’s)

5.16 Nixon Shock (August 15, 1971)

5.17 Petrodollar (1974 – Present (2015))

5.18 The Birth of Bitcoin (January 2009)

5.19 The Evolution of Money

5 The History of Money (in the U.S.)

Up to this point in the subject of money, we have seen glimpses of commodity money in ancient Egypt, in the Roman Empire, and in the British Empire–an empire so large that it was said that “the sun never set on it” [1]. If we had more time, we could review the history of money from the time of Adam to the present day but, alas, such an exhaustive endeavor is beyond the scope of this unit. So we’ll use the limited time we have to focus our view of the history of money to the last two hundred and fifty years and also restrict the geographical view of the history of money to that of the United States of America.

As you can imagine, money in colonial America was anything that had value. Money wasn’t as well defined, established, or regulated then as it is today. The most common types of money were specie/coin (hard commodity money), paper money/banknotes (representative money), or grains, tobacco, beaver skins, wampum, or other such commodity items (soft commodity money). [2] Bartering with these items was commonplace.

5.2 Continental Currency

To fund the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress authorized the printing of Continental currency, Continentals for short. Over a 5-year period (1775-1779), the Continental Congress issued $241,552,780 in Continental currency. Continentals were fiat currency with no commodity backing. By 1780, the Continental was worth 1/40 of its face value–essentially worthless. [3]

With the defeat of the British in the Revolutionary War, early American leaders now focused on setting their financial house in order.

The Coinage Act of 1792 established the U.S. Dollar as the standard unit of money with the silver dollar at its core and at a value equal to that of the Spanish silver dollar. The Act specified that the U.S. dollar would contain 371 grains (or 24.1 grams) of pure silver. [4]

The Act also established the US Mint in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where citizens were able to bring gold and silver bullion and have it “coined” free of charge.

The Coinage Act of 1834 increased the silver-gold ratio from 15:1 as specified in the Coinage Act of 1792 to 16:1. As a result, one ounce of gold was equal to $20.67. [5]

5.5 The Coinage Act of 1849 (Gold Coinage Act)

With the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, CA in 1848, the amount of gold bullion in the U.S. increased substantially. This Act authorized the minting of two new gold coins–the gold dollar ($1) and the double eagle ($20). In 1791, Alexander Hamilton had proposed both a $1 silver coin and a $1 gold coin but the gold dollar was not struck until 1849, likely due to limited quantities of gold available in the U.S. prior to the discovery of gold in ‘49. The Act formally introduced a bi-metallic dollar. It also defined the acceptable variations in quality/fineness for each type of gold coin. [6]

The Coinage Act of 1857 removed the legal tender status of foreign-minted coins like the Spanish Dollar. Only coins minted by the U.S. Mint would be legal tender going forward. This gave the U.S. government full control (a monopoly) over the money supply. [7]

5.7 Greenbacks and The Legal Tender Act of 1862

To finance the Civil War, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln issued unbacked, fiat currency called greenbacks–named for the green-colored ink used on the back of the note.

This caused a bit of a stir as the citizens of the United States were generally reluctant to accept “paper money” (fiat currency). Perhaps in an effort to assuage the electorate, Lincoln reservedly remarked: “Silver and gold I have none, but such as I have I give to thee.” [8]

California and Oregon were not amused and entirely refused to abide by the Act. This was the first time since Continentals were issued to fund the Revolutionary War that the Federal Government had issued fiat currency. [9] Like the prior issuance, this issuance would be used to fund a war.

The legality/constitutionality of the Act was litigated in the Supreme Court in 1871. Judge Salmon Chase, who was the Secretary of the Treasury (and a key supporter of the greenback issuance) when the idea of issuing greenbacks was concocted, wrote the majority opinion in favor of the issuance. [10] See conflict of interest.

The Specie Payment Resumption Act of 1875 converted the greenbacks from unbacked, fiat currency to representative money by making greenbacks redeemable for gold. [11]

5.8 The Coinage Act of 1873 (or Crime of ‘73)

The Coinage Act of 1873 prohibited the holders of silver bullion from having their silver minted into fully legal tender silver coins thus ending bimetallism and putting the U.S. solely on the gold standard. The Act effectively demonetized silver and reduced the money supply significantly as new legal tender coins could only be minted in gold.

5.9 The Gold Standard Act of 1900

The Gold Standard Act was the final nail in the coffin of the silver dollar. The Act defined the dollar as 23.22 grains of fine gold (25 8/10 grains of nine-tenths purity) and reconfirmed the price/value of one ounce of gold as twenty dollars and 67 cents ($20.67). [13]

5.10 The Federal Reserve Act (1913)

The Federal Reserve Act created a central banking system with authority given to the Board of Governors to manage the nation’s money supply and regulate banking at the local, state, and national level. Banks were previously chartered at the state level. (More about banking in the next unit.) The Act was passed on December 23, 1913–two days before Christmas–with many congressional representatives already out of town for the holiday and the remaining ones wanting to get out of town as quickly as possible so they could enjoy Christmas with their families. [14]

Prior to the Federal Reserve Act, and as outlined in this Unit, the amount of money in the financial system (the money supply) was a function of mining (work). The money supply increased as new gold (and prior to 1873, silver) was discovered and mined. New money literally couldn’t be “made” unless work was done to make it. This inelastic money supply forced prudent economic behavior and financial discipline on individuals, families, businesses, and governments. It also limited politicians’ ability to respond to economic crises since they were constrained by the requirements associated with creating money–work. Problems couldn’t simply be papered over with fiat currency.

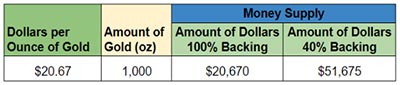

This all changed with the passage of the Federal Reserve Act. The Federal Reserve would be authorized to create an elastic money supply with dollars having a minimum 40% backing of gold instead of the previously mandated 100% backing. However, to have an elastic money supply, you also have to have elastic money and an elastic definition of the dollar too. Instead of using an inelastic/fixed definition of the dollar where $20.67 equals 1 ounce of gold, the definition of a dollar would fluctuate along with the money supply as shown in the table below.

By reducing the required amount of gold backing the dollar (representative money) from 100% to 40%, The Fed could make $51,675 ($20,670/40% or 40% of X = $20,670). That is an additional $31,005 that can be created without requiring any additional gold (or work). This allowed The Fed to inflate the money supply by 150% ($31,005/$20,670) which in turn would increase the price of gold from $20.67 ($20,670/1,000 oz gold) to $51.67 ($51,675/1,000 oz gold).

The expression of equality in 1900 (per the Gold Standard Act) was:

1 oz gold = $20.67

However, by increasing the money supply to $51,675, the price of gold also increased. Think about what would happen if the people holding all those dollars wanted to exchange their dollars (representative money) for gold (commodity money) at the rate of $20.67 per ounce of gold? (Remember, representative money is simply a claim on a commodity.) That means for every $20.67, The Fed would need 1 ounce of gold. So with $51,675 dollars in claims, that would require 2,500 ounces of gold ($51,675/$20.67 per ounce) but, unfortunately, The Fed only had 1,000 ounces of gold. Somebody would be left without their gold and that person was the person who was the last in line to redeem their claim. (This is always the cause of banking panics–too many paper claims on an insufficient amount of physical money.)

To maintain equality for each new dollar created, the new exchange rate (the price) must be $51.67 per ounce of gold ($51,675/1,000 oz).

The new exchange rate after the devaluation would be:

1 oz gold = $51.67

Or, alternatively, if you had $20.67, you could exchange it for 40% of 1 oz of gold.

The new exchange rate in dollar terms would be:

$20.67 = 0.40 oz gold

And just like in Rome when Caesar devalued the denarius, by devaluing the dollar, or changing the amount of gold backing each dollar, The Congress, by way of the Federal Reserve, caused inflation in the money supply which is always associated with, and followed by, increases in the prices of bread, circus tickets, lamb chops, and all the other goods and services in the economy. This inflationary period from 1920 – 1929 was known as the Roaring Twenties.

5.11 The Emergency Banking Act (1933)

The Federal Reserve System (The Fed) was created in response to consistent, recurring banking panics, including those in 1907, 1893, and 1873, and in response to other unsettling events associated with economic uncertainty (prices and employment). The Fed was supposed to smooth the inconsistent business cycle and prevent future panics. The exact opposite occurred. With money untethered from work, The Fed was given power to manage an elastic money supply–the ideal amount to be determined by economists and bankers and influenced by politicians and businesses. Unfortunately, having the power to do something doesn’t always equate to having the skill or ability required to do it effectively. And managing an elastic money supply proved to be quite a difficult task, as characterized by the roaring exuberance of the early ‘20s (the inflating of the bubble) that was followed by the crushing vengeance of the Great Depression at the end of the decade (the popping of the bubble).

The Great Depression reached its nadir in 1933. Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) won the U.S. presidential election in 1932 and was tasked to lead the country out of depression. On March 4, 1933, FDR was inaugurated President of the United States. Two days later, on March 6th, he declared a four-day national bank closure that closed all banks until Congress could take action to resolve the banking crisis. Three days later, on March 9th, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act that authorized The Fed to issue new currency to banks so that when reopened they would be able to meet depositors’ withdrawal demands. [15]

5.12 Executive Order 6102 (1933)

One month after enacting the Emergency Banking Act, on April 5th, FDR signed Executive Order 6102 that prohibited U.S. citizens from owning or possessing gold–including gold coins (good money). Citizens were required to deliver all gold coins, gold bullion, and gold certificates to the Federal Reserve by May 1st or be punished by a fine up to $10,000 or imprisonment up to ten years, or both. [16] In exchange for each ounce of gold confiscated by The Federal Reserve, citizens would be given $20.67 in devalued (bad money) Federal Reserve Notes (FRN). [17] See “Roosevelt’s Gold Program” at https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/roosevelts_gold_program.

With the Gold Reserve Act, Congress confiscated the gold from The Federal Reserve, which had confiscated it from U.S. citizens the prior year. The gold now belonged to the U.S. Treasury. The price of 1 oz of gold was then changed from $20.67 to $35.00–an increase of 40%. This surely displeased U.S. citizens who only got $20.67 less than a year earlier. It surely pleased gold miners and foreigners whose gold was now worth 40% more dollars overnight. Needless to say, gold flowed into U.S. coffers. [18]

It’s important to note here that the way to devalue hard commodity money is to put less of the commodity in the coin/money/currency like Caesar did to the Denarius. Devaluing representative money is even easier. You can’t put less silver in a piece of paper (Federal Reserve Note/dollar bill). It doesn’t have any silver in it. It’s a piece of paper. Instead, you simply change the price of money like Roosevelt did. Think of it like this. If the Federal Government had a million ounces of gold in 1933, they had roughly twenty million dollars. In 1934 after Roosevelt changed the price/value of gold from $20 to $35, they now had thirty-five million dollars. Roosevelt magically conjured up $15 million dollars without anyone doing any extra work and without raising taxes. Emperors, dictators, and politicians always need more money. The secret is for them to figure out how to get more money without doing any more work. This is how to get money for nothing. Once they figure that out, there’s no stopping them!

5.14 World War II and The Bretton Woods Agreement (1944)

Ten years later, Europe, Japan, and parts of Russia were decimated by fighting in World War II. The U.S. was largely unscathed with the exception of Pearl Harbor, HI. Being flush with gold and not having the expense associated with post-war rebuilding of infrastructure, the U.S. was poised to dethrone the British and their pound sterling as the world’s reserve currency.

At the end of WWII, the leaders of the victorious nations met at a ski resort in Bretton Woods, NH to hammer out the post-war global financial system. The new system would be dollar-centric with each nation’s domestic currency tied to the dollar at a fixed, but flexible, exchange rate and the dollar tied to gold at $35/oz. The dollar would be “as good as gold”. [19]

5.15 Bread, Circus, and War (1960’s)

The 50’s and 60’s saw the Korean War and the Vietnam War plus tons of deficit spending on Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” social programs.

With profligate spending on bread (social programs) and war, foreign governments became more and more concerned about the management of the dollar–to which their currencies were tied. Fearing that the U.S. government was mismanaging the dollar, they sought to exchange their dollar holdings for gold.

5.16 Nixon Shock (August 15, 1971)

Less than 30 years after the Bretton Woods Monetary Agreement, U.S. President Richard Nixon shocked the world by terminating the convertibility of dollars to gold. The Nixon Shock did to foreigners what FDR’s Executive Order 6102 did to U.S. citizens–prevented them from escaping the devaluation of the dollar by cancelling the convertibility of the dollar to gold.

From this day in August of 1971 to today, all major national currencies are fiat currency.

5.17 Petrodollar (1974 – Present (2015))

With the international financial system reeling from the Nixon shock, inflation in the U.S. started to soar in the ‘70s. Recognizing the need to reconnect the U.S. dollar to something valuable, U.S. President Nixon sent Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to Saudia Arabia to strike a deal whereby the U.S. would provide military protection to the House of Saud (and their oil resources) in exchange for the promise made by the Saudis to exclusively sell oil for U.S. dollars. [21]

Black gold (oil) instead of yellow gold would now provide quasi commodity backing of the U.S. Dollar. With oil backing the U.S. Dollar, along with its role as the International Reserve Currency, demand for U.S. Dollars would remain high and therefore interest rates would remain low.

In a world awash in worthless fully fiat currency, the U.S. dollar would at least be quasi fiat currency. Although it was not directly convertible to a fixed amount of oil, if you needed oil, you had to pay for it with U.S. dollars. [22] And as explained in Unit 2 – The Definition of Work, oil powers our entire way of life. If you wanted power, or the ability to do prodigious amounts of work (see Unit 2 – The Definition of Work), you would have to pay for work/oil power using U.S. dollars.

5.18. The Birth of Bitcoin (January 2009)

In the midst of The Great Recession, Bitcoin was born. The genesis block was mined on Saturday, January 3, 2009. The text associated with the block read: The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks. The text was a reference to the headline (Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks) of The Times (the British Daily Newspaper) on 3 January 2009. [23]

The pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto is the father of Bitcoin. He authored the paper, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” that was posted on Bitcoin.org on October 31, 2008. The identity of the real Satoshi remains unknown.

5.19. The Evolution of Money

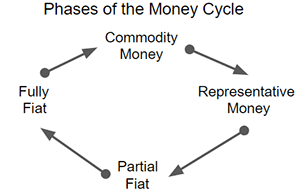

Money has followed, is following, and will follow the cycle of money as illustrated below:

At the beginning of the cycle, money is something that requires work to get/make/produce. By the end of the cycle, money is something that doesn’t require work to get/make/produce.

At some point in the future, money will evolve from the current “Fully Fiat” phase to a new “Commodity Money” phase and the cycle will start again–in the same way the denarius died and the argenteus took its place in the Roman Empire.

Summary

Money evolved/devolved from commodity money to representative money to partial fiat currency to fully fiat currency. Today, all major national currencies are fiat with the exception of the U.S. Dollar which is quasi fiat. If the U.S. Dollar ever loses its quasi commodity backing of oil, or is displaced by another currency as the primary International Reserve Currency, demand for U.S. dollars will plummet, inflation in the U.S. will skyrocket, and the standard of living for most Americans will deteriorate significantly.

Endnotes

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 20). The empire on which the sun never sets. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_empire_on_which_the_sun_never_sets&oldid=931650491

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 3). Early American currency. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Early_American_currency&oldid=929001860

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 3). Early American currency. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_American_currency#Continental_currency

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, November 20). Coinage Act of 1792. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Coinage_Act_of_1792&oldid=927096314

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, August 16). Coinage Act of 1834. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Coinage_Act_of_1834&oldid=911023700

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, March 28). Coinage Act of 1849. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Coinage_Act_of_1849&oldid=889796134

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, March 28). Coinage Act of 1857. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Coinage_Act_of_1857&oldid=889936811

- Leigh, P. (2015). Lees lost dispatch and other civil war controversies. Yardley, PA: Westholme.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 6). Greenback (1860s money). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Greenback_(1860s_money)&oldid=929488829

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, June 28). Legal Tender Cases. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legal_Tender_Cases#Background_about_constitutionality_of_paper_money

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, September 8). Specie Payment Resumption Act. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Specie_Payment_Resumption_Act&oldid=914585253

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 8). Coinage Act of 1873. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Coinage_Act_of_1873&oldid=929810168

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 9). Gold Standard Act. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gold_Standard_Act&oldid=929976375

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 16). Federal Reserve Act. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Federal_Reserve_Act&oldid=930972271

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, October 20). Emergency Banking Act. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Emergency_Banking_Act

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 19). Executive Order 6102. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Executive_Order_6102

- Richardson, G., Komai, A., & Gou, M. (2013, November 22). Roosevelt’s Gold Program. Retrieved from https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/roosevelts_gold_program.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, November 1). Gold Reserve Act. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gold_Reserve_Act

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 18). Bretton Woods system. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bretton_Woods_system

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, August 29). Nixon shock. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Nixon_shock

- Tun, Z. (2015, July 29). How Petrodollars Affect The U.S. Dollar. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/articles/forex/072915/how-petrodollars-affect-us-dollar.asp

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 7). Petrodollar warfare. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Petrodollar_warfare

- Wikipedia contributors. (2014, December 19). History of bitcoin. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=History_of_bitcoin

ADDITIONAL READING

The Great Deformation – David Stockman

The transformation of money from Commodity money to Rep Money to fiat currency is well chronicled in this book.