Unit 4 - The Types of Money

Learning Objective: Understand and be able to explain the different types of money, currency, and cryptocurrency.

Recall from Unit 1 that after Adam was expelled from the Garden of Eden, food was his primary concern. He had clothing–a coat of skins–provided by The Lord. Shelter was also a concern but not having shelter wouldn’t kill him right away. He would have to work to get food. It’s no wonder that the first type of money was soft commodity money–things that are grown.

There are two types of money: commodity money and representative money.

Commodity Money – money whose value is derived from the utility or usefulness that the commodity provides. It is the actual commodity itself that is used as money. [1]

Types of Commodity Money:

- Soft Commodities – things that are grown: wheat, barley, sugar, soybeans. Cain’s wheat is an example of soft commodity money.

- Hard Commodities – things that are mined: gold, silver, platinum, palladium. Caesar’s denarius is an example of hard commodity money. A U.S. silver dollar is another example. American Eagle coin contains a minimum of one troy ounce of .999 pure silver. The weight and purity of each Eagle Silver coin is backed by the US government.

- Other Commodities – beaver pelts, cigarettes, shoes–anything that takes work to produce.

Representative Money – money whose value is derived from the underlying item for which it is represented. It is generally a claim on a commodity. [2]

Types of Representative Money

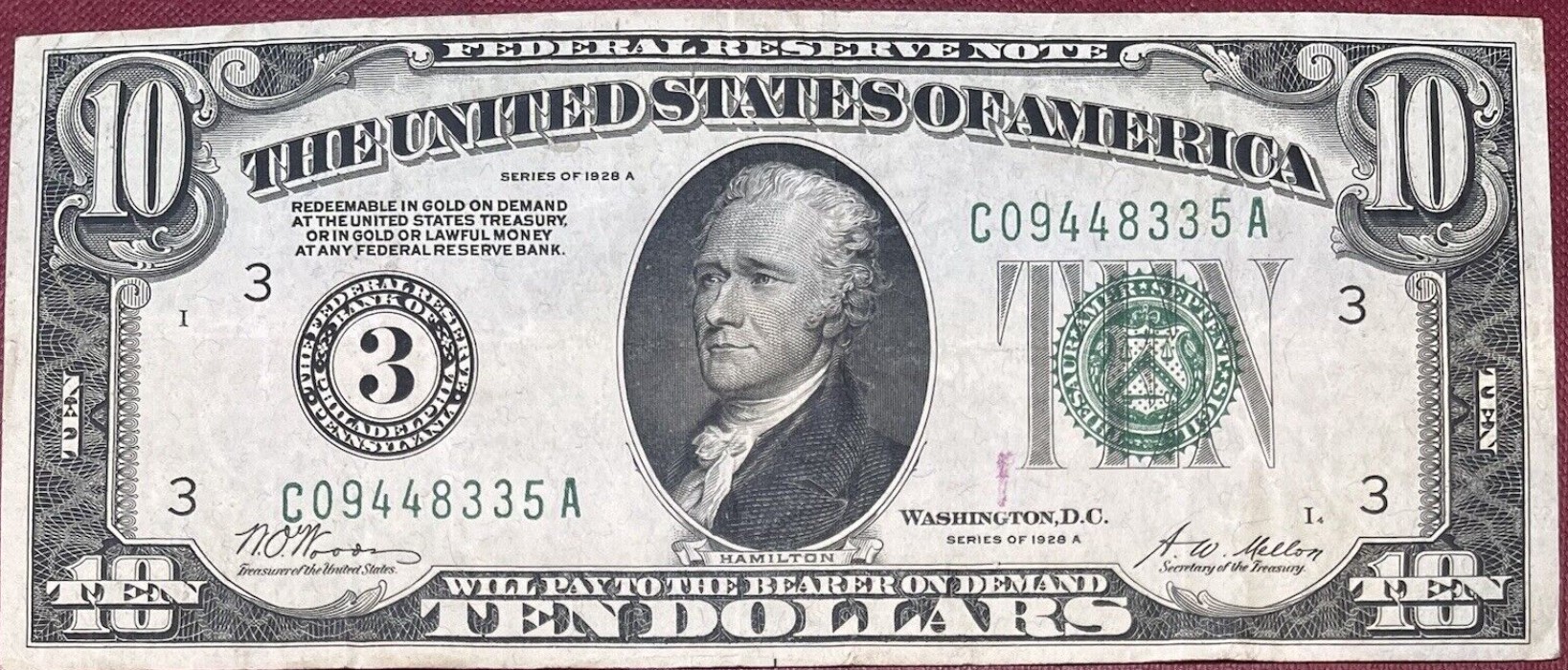

- Banknotes, certificates, or tokens that have commodity backing are representative money. When first introduced, the US Dollar was redeemable for a fixed amount of gold. It was representative money.

Fiat Money – “a currency without intrinsic value that has been established as money, often by government regulation.” [3]

Types of Fiat Money:

- Partial Fiat – currency backed by a commodity but not exchangeable for the actual commodity. See Swiss franc. Prior to May 1, 2000, the Swiss franc was legally required to have at least 40% backing by gold reserves. [4]

- Quasi/Implied Fiat – currency that has implied commodity backing. As the global reserve currency, the US dollar is quasi-fiat because although it is not backed by a commodity, it must be used in international trade when buying commodities–particularly oil. [5] See Petrodollar.

- Fully Fiat – currency that has neither commodity backing nor any other real-world, tangible, backing by something that has value and for which is work required to get the thing. All national currencies are fully fiat with one exception–the US dollar which is quasi-fiat.

Cryptocurrency – a decentralized, peer-to-peer digital currency that is designed to function as a medium of exchange, unit of account, and store and measure of value. It uses strong encryption to validate financial transactions. For full transparency, all transactions are stored in a publicly accessible, distributed ledger database called a blockchain.[6] Cryptocurrency units are created by mining and a finite number of coins can be mined. The digital mining process is a virtualization of the mining that is done in the real world. Mining rigs are highly specialized computers that are capable of performing high-speed decryption algorithms to create new blocks on the blockchain. A proof-of-work algorithm awards miners new units of cryptocurrency when financial transactions are validated and put in blocks. [7] The blocks are then added to the blockchain. In essence, you can think of cryptocurrencies as digital gold. [8]

Types of Cryptocurrency

- Bitcoin is generally considered the original cryptocurrency (the OG). Thousands of other cryptocurrencies have been created following the success of Bitcoin. They are referred to as altcoins. Some of these alternative coins share the same DNA as Bitcoin–they are cryptographic in nature, use blockchain technology, and require proof-of-work algorithms. [9] Other coins are a dog and were created as joke.

- Digital Fiat Currency – a digital currency whose value is pegged, or tethered, to the value of a national, fiat currency. [10]

Types of Digital Fiat Currency

- Stablecoins

- Tether (USDT)

- USD Coin (USDC)

- Facebook Libra

4.2 The Definition of Money

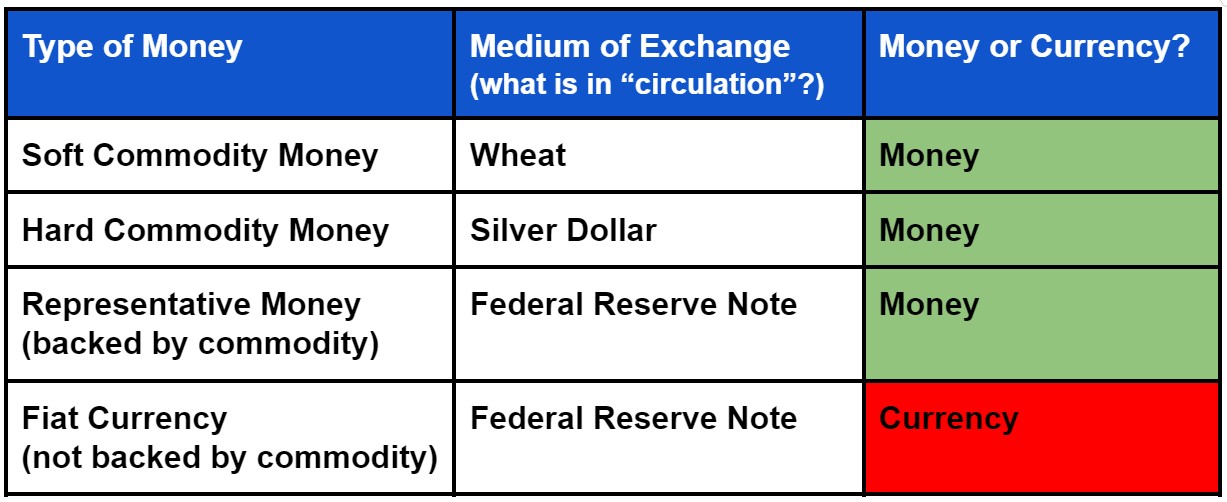

Remember the definition of money from Unit 1? Money is a Store of Value, Unit of Account, Medium of Exchange (SUM), and something that takes work to get/make/manufacture. It’s something for which you would exchange your work. In the above list of the types of money, are there any types that don’t meet the definition of money? Would you be reluctant to exchange your work for any of these types of money?

4.3 The Definition of Currency

Fiat money is not real money. It can function as a Unit of Account and a Medium of Exchange, but it’s not a Store/Measure of Value, and, most importantly, it doesn’t take work to produce. It is produced by dictate/diktat as defined by the word itself: [11]

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fiat

As a medium of exchange, it can be termed fiat currency. Currency means “in circulation”. [12] Fiat currency is essentially fake representative money. It is representative money that has had its commodity backing removed but still “circulates” as money; however, it is not actual money in the true sense of the word. That is the key difference between currency and money.

This is Representative Money:

This is fiat currency:

What’s the difference?

The following chart shows the differentiation between money and currency:

4.4 The Hierarchy of Money (and Currency)

Commodity money is the most valuable money and is therefore at the top of the money hierarchy. Representative money is commodity money with paper money/notes used as a medium of exchange due to better portability. The following chart shows the types of money in descending order by value:

4.5 The Amount of Work in Money

Recall from Unit 1, that a function of money is as a store of value and a measure of value. In Unit 3, we defined value as something that has scarcity, utility, intrinsic and extrinsic value, and takes work to get. Money is a measure of value. How much value is in each type of money? One measuring stick for assessing value is the amount of work in each type of money

The following table shows the estimated amount of work in each type of money:

The following chart displays the amount of work in each type of money graphically:

If you could choose to be paid for your work in any of these types of money (or currency), which one would you choose? Apparently, John Pierpoint (JP) Morgan would choose hard commodity money. While testifying before Congress in 1912, he said “Money is gold, and nothing else” [21]

For people who are reluctant to choose lower value fiat currencies, national governments enact legal tender laws to enforce their acceptance. To further prevent the use of commodity money, governments prohibit the use of money they deem contrary to their objectives. Owning gold was outlawed in the U.S. by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 by Executive Order 6102. [22]

Recognizing the historical use of gold as money, and knowing it should be legal to use it as such, notwithstanding the actions of the U.S. Federal government, states are starting to modify legal tender laws to remonetize gold and silver. [23]

4.7 Gresham’s Law

“Bad money drives out good money” is the essence of Gresham’s Law. [24] “Bad” money is money with a[n] intrinsic/commodity/melt value (the value of the metal of which it is made) noticeably lower than its face/nominal value.

“Good” money is money with minimal, if any, difference between its nominal/face value and its intrinsic/commodity/melt value.

When bad money is in circulation alongside good money, the bad money will drive out the good money because the face/nominal value of good money is lower (sometimes much lower) than its intrinsic/commodity/melt value.

Bad money is the byproduct of governments removing precious metal content from commodity money and then using legal tender laws in an attempt at passing it off as an equivalent to the circulating good money. It is exactly what Caesar did to the denarius. And it’s not an uncommon phenomenon. The infamous King Henry VIII did it too.

To pay for foreign wars and his lavish lifestyle, King Henry VIII orchestrated “the great debasement” (1544–1551). [25] of the shilling (and other coins of the realm). He created bad money by reducing the precious metal content in coins by more than 50%. Over time, the good shillings with the pre-debased higher silver content disappeared from circulation. After acceding to the throne, Queen Elizabeth wanted to know what happened to the “good” shillings. As a financial agent to the crown in Antwerp, Sir Thomas Gresham explained “that good and bad coin cannot circulate together”. England was left with the bad money while all of the good money ended up in Belgium and other countries, “all your fine gold was convayed out of this your realm.” [24]

The “bad” shilling’s face value was 1 shilling and the melt value of the silver in the bad shilling was 6 pence (12 pence = 1 shilling). Thus the melt value was lower than the face value. That’s bad money. In contrast, the “good” shilling that had the original amount of silver, still had a face value of 1 shilling but the melt value of the silver in the good shilling was 18 pence (1 shilling and 6 pence). That’s good money. Really good money. So people hoarded the good shillings–recognizing their greater melt value. They wouldn’t spend/use them.

The same thing happened here in the U.S. The fiat dollar bill has driven out hard commodity money like U.S. silver eagles. The face value of a silver eagle is $1. The melt value as of 2015 is $17 ($24 in 2023). So nobody uses silver dollars. They hoard them. That’s the essence of Gresham’s Law. Bad money drives out good money when legal tender laws attempt to make them equal in value.

4.8 When Money Failed

What is the best type of money?

Surely you know the story of Joseph and his amazing technicolor dream coat? But you probably only heard the first half of the story–up to the part when Joseph is reunited with his brothers and father. The second half is where it gets dicey.

Joseph was his father’s favorite son. His father, Jacob/Israel, gave him a coat of many colors. This, along with other irritations, made his brothers both jealous and envious of Joseph so they devised a scheme to get rid of the dreamer. As the story goes, they didn’t have the heart to kill him so they threw him in a pit and then sold him to a caravan of Ishmaelite merchants heading to Egypt.

In Egypt, Joseph was bought as a slave by Potiphar. After being falsely accused by Potiphar’s wife, Joseph was thrown in jail. It wasn’t long before Joseph had gained the trust of the jailer and was in charge of all the prisoners. In prison, Joseph ran into Pharaoh’s butler and baker who somehow had offended the King. They both had dreams that Joseph interpreted correctly.

Two years later, Pharaoh dreamed about kine/cows and corn but didn’t know what to make of the dreams. With the butler restored to his post, and remembering that Joseph had interpreted his dream correctly, he suggested that Joseph be given a chance at interpreting Pharaoh’s dreams. As you know, Joseph interpreted the dreams to mean that there would be seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine. Knowing Joseph to be inspired and directed by God, Pharaoh appointed him to see Egypt through the 14-year crisis.

Back in Canaan, Jacob/Israel and his remaining 11 sons were getting hungry because “the dearth was in all lands; but in all the land of Egypt there was bread.” (Genesis 41:54) So Jacob sent 10 of his sons to Egypt to get bread. Joseph was eventually reunited with his brothers and his father and his family all moved to Egypt and they lived happily ever after. At least that’s where the Andrew Lloyd Webber version ends. But the story actually continues…

As the famine intensified, Egyptian city slickers found themselves out of food. Joseph didn’t just hand out wheat for the asking though, he sold wheat for money:

“Joseph collected all the money that was to be found in Egypt and Canaan in payment for the grain they were buying, and he brought it to Pharaoh’s palace.” (Genesis 47:14)

When the people ran out of money, they went back to Joseph and pleaded with him saying:

“And when money failed in the land of Egypt, and in the land of Canaan, all the Egyptians came unto Joseph, and said, Give us bread: for why should we die in thy presence? for the money faileth.” (Genesis 47:15)

At that point, Joseph still didn’t give them wheat without anything in return. He resorted to barter:

“And Joseph said, Give your cattle; and I will give you [wheat] for your cattle, if money fail. And they brought their cattle unto Joseph: and Joseph gave them bread in exchange for horses, and for the flocks, and for the cattle of the herds, and for the asses: and he fed them with bread for all their cattle for that year. (Genesis 47:16-17)

By the next year, the poor people were out of money, out of cattle, and out of food so they sold themselves as slaves:

“buy us and our land for bread, and we and our land will be servants unto Pharaoh: and give us seed, that we may live, and not die, that the land be not desolate.” (Genesis 47:19)

So by the time the famine ended, Joseph had purchased all of Egypt. Former city slickers were transitioned into farmers. Joseph loaned them seeds and land to cultivate. They were then taxed one-fifth (20%) of their yield to repay their loans.

After seven years the famine ended and a new Pharoah who “knew not Joseph” took over. Once the economy got back on track and the Egyptians got their freedoms back, they turned their ire towards the children of Israel and blamed them for their hardship and suffering–eventually turning the tables and enslaving the Israelites.

It’s important to note that the Egyptian money (hard commodity money–gold and silver) didn’t fail. The people’s supply of money failed. By exchanging wheat (soft commodity money) for hard commodity money, “Joseph collected all the money that was to be found in Egypt and Canaan.” It failed in the sense that the Egyptians didn’t have any more money. Joseph had it all.

So, what’s the best type of money? In times of plenty (of food), hard commodity money because it has a longer shelf life and isn’t subject to spoilage. In times of famine, soft commodity money because, as the saying goes, “you can’t eat gold”. [26]

Summary

Soft and hard commodity money, representative money, and commodity-backed cryptocurrencies are types of money. Fiat currency is representative money that has been stripped of its commodity backing. Fiat currency circulates like representative money but is really fake representative money. The best type of money is money that functions well as a store of value, a unit of account, and a medium of exchange. Commodity money has performed these functions for 5,000+ years. The way forward is backward.

Endnotes

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, November 10). Commodity money. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Commodity_money&oldid=925502228

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, June 20). Representative money. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Representative_money&oldid=902692859

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, November 15). Fiat money. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fiat_money&oldid=926305692

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, November 19). Swiss franc. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Swiss_franc&oldid=926953400 See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swiss_franc#cite_note-16

Wikipedia contributors. (2019, September 23). Petrocurrency. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Petrocurrency&oldid=917371366

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, November 17). Cryptocurrency. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cryptocurrency&oldid=926662299

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, November 15). Proof of work. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Proof_of_work&oldid=926223482

Popper, N. (2016). Digital gold: Bitcoin and the inside story of the misfits and millionaires trying to reinvent money. New York: Harper. See also: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23546676-digital-gold

Wikipedia contributors. (2016, November 20). Bitcoin. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bitcoin&oldid=927140927

Wikipedia contributors. (2017, October 26). Stablecoin. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Stablecoin&oldid=923190429

“Fiat”. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fiat

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, November 15). Currency. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Currency&oldid=926293744

Hicks, S. (2014, October 17). Today in Energy. Energy for growing and harvesting crops is a large component of farm operating costs. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=18431

“Gold supply and demand statistics”. (2014, November 5). Retrieved from https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/gold-supply-and-demand-statistics

“Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index”. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.cbeci.org/

“Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index”. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://digiconomist.net/bitcoin-energy-consumption

“Annual Production Reports”. (n.d.). BUREAU OF ENGRAVING AND PRINTING. U.S. Department of the Treasury. Retrieved from https://www.moneyfactory.gov/resources/productionannual.html

McCook, H. (2014, July 10). Under the Microscope: The Real Costs of a Dollar. Retrieved from https://www.coindesk.com/microscope-real-costs-dollar

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, October 24). Utah Data Center. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Utah_Data_Center&oldid=922855008

Buchanan, D. (2013, February 10). “Money Is Gold, and Nothing Else”. Retrieved from https://schiffgold.com/commentaries/money-gold-nothing-else/

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, October 4). Executive Order 6102. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Executive_Order_6102&oldid=919512657

Maharrey, M. (2017, August 2). Retrieved from https://tenthamendmentcenter.com/2017/08/02/status-report-states-take-on-the-feds-money-monopoly/

Wikipedia contributors. (2014, November 19). Gresham’s law. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gresham%27s_law&oldid=926970342

Wikipedia contributors. (2019, October 5). The Great Debasement. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Great_Debasement&oldid=919768767

- Christenson, G. (2016, August 2). You Can’t Eat Gold! Retrieved from https://www.sprottmoney.com/Blog/you-cant-eat-gold-gary-christenson.html