Unit 3 - The Value of Money

Learning Objective: Be able to explain the value of money, the process by which money is devalued, and the end result of the devaluation process.

Unit Outline

3.1 The Definition of Value

3.2 The Source of Value

3.3 How to Add Value

3.4 How to Remove Value from Money

3.5 Work and Value

3.6 Devaluation, Debasing, and Debauching

3.7 Measuring Inequality

3.1 The Definition of Value

Recall from Unit 1 that one of the functions of money is to be a store and measure of VALUE. So what is value?

Value, as defined by Webster, is:

- the monetary worth of something [the price]

- a fair return or equivalent in goods, services, or money for something exchanged

- something (such as a principle or quality) intrinsically valuable or desirable [1]

3.2 The Source of Value

What makes things valuable?

Sources of value include:

- SCARCITY – the state of being scarce, rare, or limited–not abundant or easily obtainable. Economics is the allocation of scarce resources.

- UTILITY – the state of being scarce, rare, or limited–not abundant or easily obtainable. Economics is the allocation of scarce resources.

- INTRINSIC VALUE – internal value that originates in the thing itself. Wheat has intrinsic value. It has value in itself as food. It can be consumed for calories to do work.

- EXTRINSIC VALUE – external value that is conveyed on a thing. The Eucharist has extrinsic value. It has external value conveyed upon it by believers in Jesus Christ who see it as a representation of the body of Christ. It is more than just a piece of bread with intrinsic value for the purpose of sustaining physical life. [2]

The best type of money has all of the above-mentioned sources of value but in addition to scarcity, utility, and intrinsic and extrinsic value, the fact that it takes work to produce money is a key factor as to what makes money truly valuable.

3.3 How to Add Value

To make something valuable, or to add value to something, requires work.

As stated in Unit 1, valuable products don’t randomly and spontaneously organize themselves into something valuable. According to the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics, things are constantly breaking down. [3] Adding work, or energy, to something can halt this natural process. Enough work/energy added to something produces a valuable product.

The process of producing a loaf of bread is an example of adding value to a thing. Bread is produced through a series of value-added work including (1) a farmer who plants and harvests the wheat, (2) a miller who grinds the wheat into bread flower, and (3) a baker who mixes the wheat and other ingredients to form a loaf of bread and then bakes it.

If adding work to something makes it more valuable, then removing work from something, or substituting valuable components with less valuable components in a product, will make it less valuable.

“Your silver has become dross, your fine wine is diluted with water,” said the prophet, Isaiah. How did silver become dross and why was fine wine diluted with water in Jerusalem in 700 BC, as recorded by Isaiah? Instead of selling fine wine, merchants diluted the wine with water so they would have more to sell. And then they likely attempted to sell the diluted wine for the same price as the fine wine. Brilliant! The diluted wine should have cost less because it is less valuable. The same thing happened to their silver coins but instead of using the Israelite’s example of silver becoming dross, we’re going to use the more famous and better-known Roman example of silver becoming dross.

3.4 How to Remove Value from Money

The devaluation of the Roman denarius (D) by Caesar is a classic example of how to devalue, or to remove work from, money. Here is how Caesar did it:

It takes work to mine silver. Additional work is required during the process of minting coins.

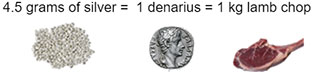

Shortly before the meridian of time, and when the Roman Republic was transitioning into the Roman Empire (45 B.C.), the denarius contained 4.5 grams of silver. [4] The value of 1 denarius was equal to the value of 4.5 grams of silver. Although we don’t know exactly the price of a loaf of bread or a lamb chop at this time, let’s assume that the price of 1 kg of lamb chop was 1 denarius. This equality can be expressed as:

According to the Transitive Property of Equality, if A (silver) = B (denarius) and B = C (lamb chop), then A = C.

The cost of running an empire was expensive. As emperor, Caesar constantly needed more money to conquer the world and pacify the plebians. How did he make more money?

With 1,000 grams of silver, Caesar could mint 222 denarii (1,000 grams of silver/4.5 grams per denarius).

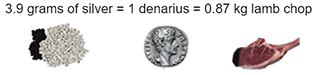

By reducing the amount of silver in each denarius from 4.5 grams to 3.9 grams, Caesar could now make 256 denarii (1,000 grams of silver/3.9 grams per denarius) producing 34 more denarii (256-222) without requiring any additional work from miners or minters. This action, unfortunately, would inflate the money supply by 15% (34 new denarius/222 original denarii), but only Caesar would know initially (until the information was leaked).

The new value of the denarius after the devaluation would be:

1 denarius = 3.9 grams of silver

Since A = C, if A is reduced by 13%, C must be reduced by the same amount to maintain equality.

The expression of equality is now:

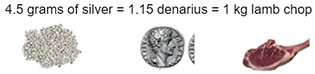

Alternatively, if you want 1 kg of lamb chop, you now have to pay D1.15 15% more denarius so the expression of equality would be:

So the result of the devaluation of the denarius is a reduction in the amount of food you can buy (1 kg to 0.87 kg of lamb chop) or an increase in the price of the original amount of food (D1 to D1.15).

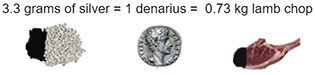

Over time, Caesar continued to devalue the denarius. After another 100 years of war, free bread, and circuses, Caesar needed even more money so the silver content in the denarius was reduced from 3.9 grams to 3.3 grams. What was the result?

The previous expressions of equality:

4.5 grams of silver = 1.15 denarius = 1 kg lamb chop

3.9 grams of silver = 1 denarius = 0.87 kg lamb chop

The exchange rate, as dictated by Caesar, is now:

3.3 grams of silver = 1 denarius

The denarius was devalued 15% ((3.9 – 3.3)/3.9)

To maintain the previous state of equality (1 denarius = 3.9 grams of silver = 0.87 kg lamb chop), market participants will react by decreasing the amount of lamb chop by an equal amount as the decrease in the value of the denarius (15%).

The new expression of equality is now:

Alternatively, if you wanted a full kg of lamb chop, you now have to pay D1.36 (15% more) so the expression of equality is:

It’s when Caesar devalues the denarius that inequality ensues. Market participants then have to decide whether to raise prices for their products, reduce the amount of product in each package (package downsizing), or do some combination of both.

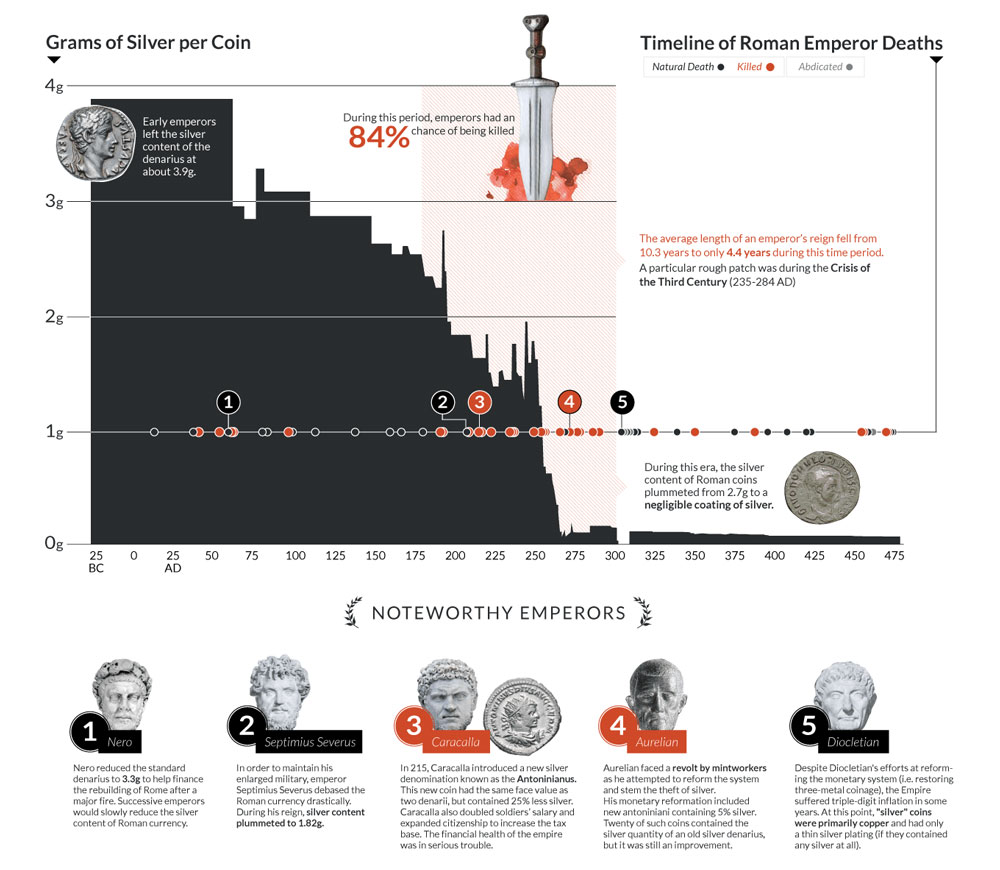

Over the span of a few hundred years, the silver content in the denarius was reduced from 3.9 grams to 0.5 grams as illustrated in the chart below: [5]

Chart Source: The Money Project

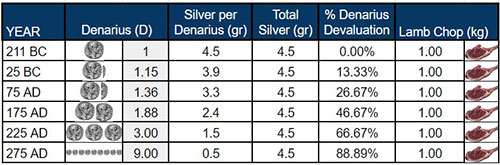

By 275 AD, if you wanted 1 kg of lamb chop, it would cost D9 instead of D1, as shown in the table below:

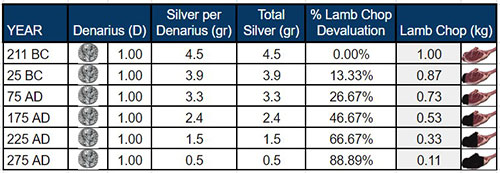

If equality (4.5 grams of silver = 1 kg of lamb chop) is maintained, the 1 denarius that originally purchased 1 kg of lamb chop would now only be able to purchase 0.11 kg of lamb chop, as shown in the table below:

Once the denarius was fully devalued (worthless) by Caesar, around 300 AD, it was replaced by the Argenteus which means, ironically, silver–of which it was made. [6]

3.5 Work and Value

With Caesar regularly introducing inequality as evidenced in the loss of the value (purchasing power) of the denarius, it’s important to remember that what is also happening is that the work of miners, minters, shepherds, teachers, and every other working person in Rome is also being devalued. In the preceding section, we looked at how much silver was in each denarius over time, but keep in mind that the amount of silver is representative of some amount of work. How much power/work does it take to mine one gram of silver?

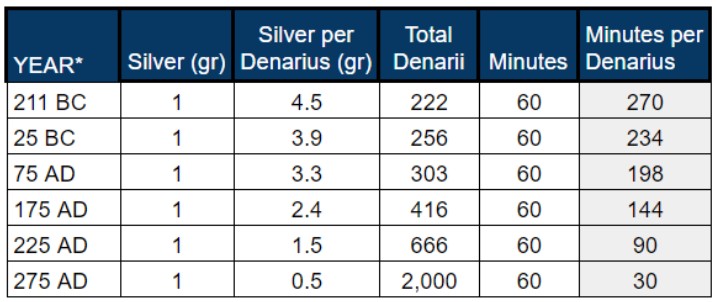

For simplicity’s sake, let’s say it takes 1 hour of mining work to get 1 gram of silver. Each gram of silver therefore takes 1 hour of mining. We’ll ignore the amount of work required to convert the raw silver into a denarius and just say each denarius takes 1 hour of work to produce. After Caesar initially devalues the denarius, he can make 34 more denarii (256 total) with 1,000 grams of silver and still only 1,000 hours of work.

Prior to the devaluation, it would have required working 270 minutes to mine 4.5 grams of silver to make 1 denarius:

60 minutes/gram of silver * 4.5 grams/denarii = 270 minutes per denarius

By the end of the devaluation of the denarius, when there was only 0.5 grams of silver in each denarius–not much left to devalue–the amount of work in each denarius was only 30 minutes (down from 270 minutes originally) as shown in the chart below:

Ideally, money is used to ensure that an equivalent amount of work, or measure of value, is exchanged in each transaction with a buyer and seller. Whether you produce silver as a miner, sheep as a shepherd, lamb chop as a butcher, or smart students as a teacher, these products all require work. As much as possible, (and it’s very difficult to get it exactly right), a key measurement for determining the exchange rate market participants use to determine the value of each product is the amount of work contained in each product.

In a productive society where people work, one hour of mining may be equal to one hour of shepherding. One hour of shepherding may be equal to 1 hour of butchering. Two hours of butchering may be equal to one hour of teaching, and so forth.

If you just had a heart attack, ten hours of mining might be worth five minutes of doctoring!

3.6 Devaluing, Debasing, and Debauching

Devaluing, debasing, and debauching the currency all mean the same thing. The famous economist, John Maynard Keynes, said:

“Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.” [7]

What did Keynes think Lenin was “certainly right” about? A few paragraphs before this, Keynes writes this:

“Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the capitalist system was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security but [also] at confidence in the equity of the existing distribution of wealth.” [7]

3.7 Measuring Inequality – The Gini Coefficient

What was the level of inequality that existed after the end of Caesar’s continual devaluation of the denarius?

Corrado Gini was an Italian statistician and sociologist. He developed a model for measuring inequality in society. Gini’s method for measuring inequality was published in 1912 in a paper titled Variability and Mutability. [8] This method is still used today and, in honor of Mr. Gini, is referred to as the Gini Coefficient. A Gini coefficient of 0 indicates perfect equality, whereas a coefficient of 1 indicates perfect inequality. According to the World Bank, the Gini index for the U.S. in 1980 was .346 (or 34.6 on the world bank scale (where 0 is equality and 100 is inequality)) and in 2015 it was 41. [9]

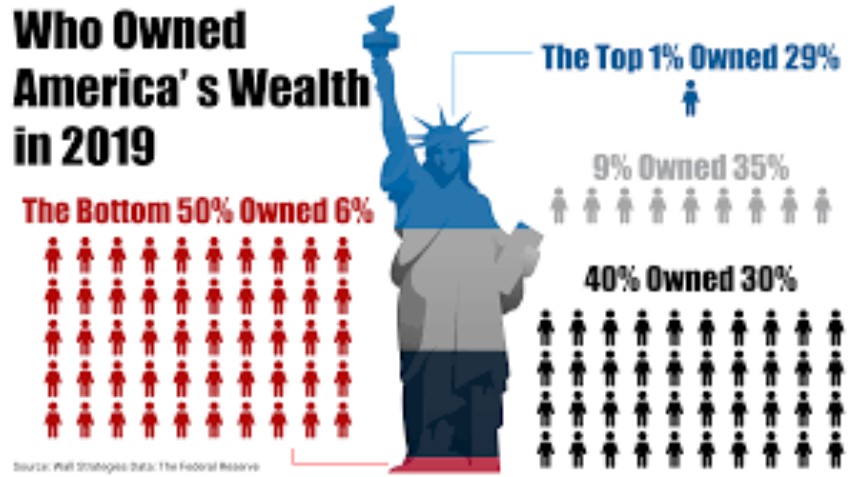

In 2019, the top 1% of the population owned 29% of total household wealth in America. The chart below shows the breakdown for the rest of the population:

Summary

The value of money comes partially from its scarcity, utility, and intrinsic and extrinsic value. But money is valuable mostly because it takes work to get/make/manufacture. To devalue money, simply remove work, as Caesar did. Inequality results when changes to the equality established by money in the form of pricing, and as used by market participants when they exchange products and services, are altered for political expedience or to enrich a portion of society.

Endnotes

- “Value”. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/work

- Wikipedia contributors. (2015, November 11). Eucharist. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Eucharist&oldid=925713022

- Wikipedia contributors. (2015, November 11). Second law of thermodynamics. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Second_law_of_thermodynamics&oldid=925634629

- Wikipedia contributors. (2015, October 1). Denarius. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Denarius&oldid=919035390

- Desjardins, Jeff. (2016, March 17). Deaths of Roman Emperors vs. Coinage Debasement. Retrieved from http://money.visualcapitalist.com/deaths-roman-emperors-vs-silver-coin-content/

- Wikipedia contributors. (2015, October 1). Argenteus. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Argenteus&oldid=918986105

- Wikipedia contributors. (2019, September 5). The Economic Consequences of the Peace. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Economic_Consequences_of_the_Peace&oldid=914161264

- Wikipedia contributors. (2015, November 12). Gini coefficient. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gini_coefficient&oldid=92577444

- “GINI index (World Bank estimate) – United States”. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=US

- Wikipedia contributors. (2015, October 31). Wealth inequality in the United States. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wealth_inequality_in_the_United_States&oldid=923913618